The Cross and the Stained Glass Window | Lent 1 | March 1

https://joelssermons.files.wordpress.com/2020/03/20200301sermon.mp3

Texts: 1 Corinthians 1:18-20; 2:1-5

Speaker: Joel Miller

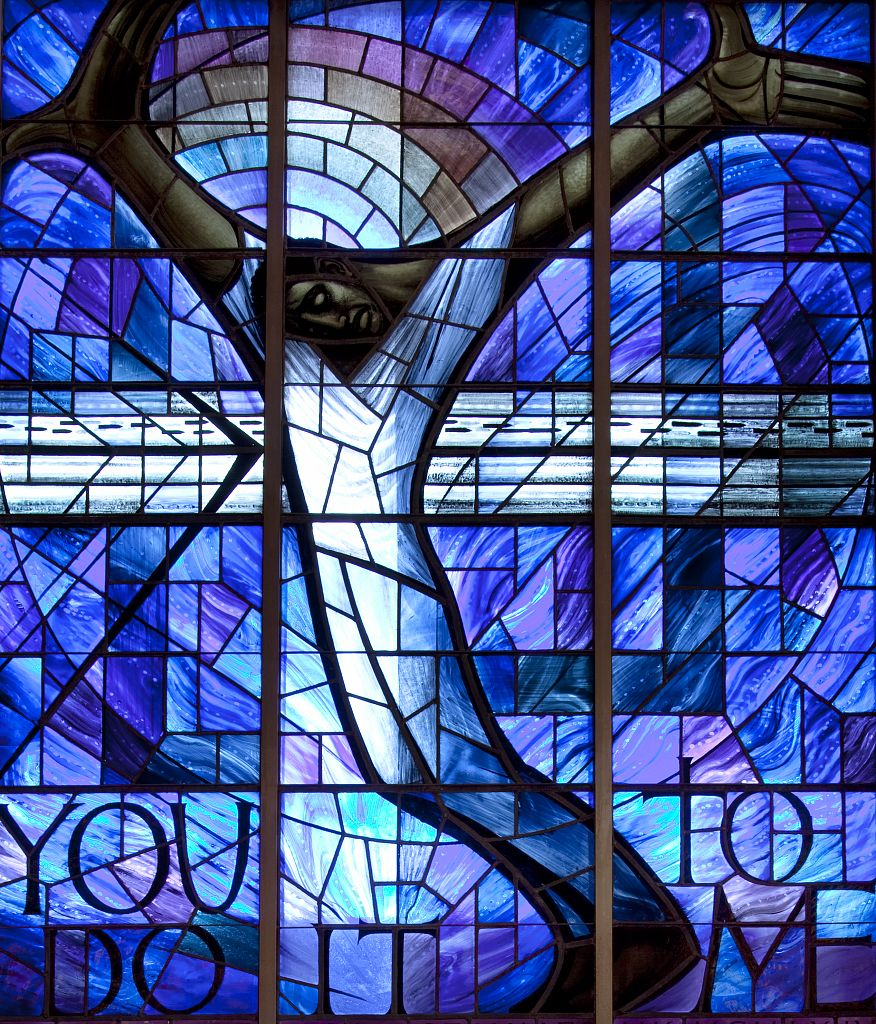

The image behind me and on your bulletins is a stained glass window in the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. That’s the church that was bombed in 1963. It was a Sunday morning in September, and there were about 200 people in the building when the bomb exploded. Four black girls were killed. Addie Mae Collins, age 14. Cynthia Wesley, age 14. Carole Robertson, age 14. Denise McNair, age 11.

The stained glass window was a gift from a Welsh artist. He was so moved by the tragedy that he raised money throughout Wales – especially inviting children to donate – in order to create this window as a permanent installation in the church. It was one of the first public depictions of a black Christ in the deep South.

One of its messages is told in the positioning of the hands. The left hand is held open, a sign of openness, of welcome, of surrender to the will of God. The right hand is held up as if holding off the very forces of evil themselves. A sign of resistance and refusal to have one’s humanity diminished by the hatred and violence directed against it.

Another message is in the writing at the bottom – five words, drawn from Matthew chapter 25. “You do it to me.” That’s the passage where Jesus tells the parable in which both the sheep and the goats learn that whatever they did to “the least of these” they have done it to Christ. Feeding the hungry, welcoming the stranger, clothing the naked, visiting the sick and imprisoned. Whatever you have – or haven’t done – to these “You do it to me.”

To have those words beneath a crucified Christ in a church where four girls were murdered…

Kitchen, casket, mountain, mundane | February 23

https://joelssermons.files.wordpress.com/2020/02/20200223sermon.mp3

Texts: Matthew 17:1-13, 2 Peter 1:16-19

Soon after his 27th birthday, a minister in Alabama faced the most fearful day of his young life. He received a phone call around midnight. The person on the other line threatened to bomb his house if he didn’t leave town in the next three days. Also in the house were the minister’s wife and their baby daughter.

Less than two months prior he had been selected to lead the first ever large-scale demonstration against racial segregation in the US. A fellow leader later reflected that the advantage of choosing him as leader was that he was so new to the city and this kind of struggle that he “hadn’t been there long enough to make any strong friends or enemies.”

But now he had made enemies, and he knew that the threat against him and his family was real.

After hanging up the phone he was overcome with fear. He couldn’t sleep. He got up from his bed and went to the kitchen. He prayed out loud: “Lord, I’m down here trying to do what’s right…But Lord I must confess that I’m weak now, I’m faulting, I’m losing my courage.” In the stillness of the dark kitchen, he heard a voice come back at him: “Martin, stand up for righteousness. Stand up for justice. Stand up for truth. And lo I will be with you, even to the end of the world.” (1)

This was Montgomery, January 1956, and it was Martin and Coretta, and little Yolanda King in that house. Rosa Parks had already refused to give up her seat on the bus. She was the leader who said King was a good choice because he had neither friend nor enemy in town, yet.

The Montgomery bus boycott is frequently referenced as the event that launched…

“The fast that I choose” | February 8

Text: Isaiah 58:1-12; Mathew 5:13-20

Speaker: Joel Miller

In Isaiah chapter 58, the prophet is in full prophet mode, dialed up to 10. It begins as if the Lord is giving Isaiah a bit of a pep talk, a locker room huddle of sorts before the prophet steps out and does his prophetic thing. “Shout out loud, do not hold back! Lift your voice life a shofar! Announce to my people their rebellion, to the house of Jacob their sins.”

And this is what Isaiah does.

As the prophets before and after him did, Isaiah directs his outcry not against those outside the community – enemy armies, foreigners, immigrants, but on the moral and spiritual condition of those inside the community – his own people.

Walter Brueggemann has taught that the role of the prophet is to criticize the status quo, and then energize toward a new, life affirming future. Criticize and energize. We can imagine those as the final words of every pep talk every prophet ever got from the Lord.

Isaiah focuses his shout-like-a-shofar message on the practice of fasting. How the people were abusing this religious practice – abusing each other while engaging in this practice. How they were approaching it as some kind of quid pro quo arrangement for divine favor. I do this for you – carry out this rigorous act of fasting – and you, God, do a little something for me.

But God isn’t playing along, and the people are upset.

Isaiah is upset.

He points out that these fasters who are lying around in sackcloth and ashes might want to start by paying their workers a fair wage — and this is where he starts to turn the corner toward the energize part….true fasting, he declares, is loosening the bonds of injustice, letting the oppressed go free, making sure the hungry…

Coming of age in the age of Babel’s Tower | February 2

Text: Genesis 11:1-9

Speaker: Joel Miller

We humans have a long history of migration and settlement. If you want to go way back, there’s evidence human species have been wandering across continents and over waters for at least two million years. More recently, a mere 70,000 years ago or thereabouts, migration out of Africa eventually led to a dispersal of modern humans just about everywhere we can survive. As groups migrated, settled, and migrated again, they formed unique cultures and languages, sometimes developing in isolation, sometimes intermingling with near and even far away peoples. Then, about 500 years ago, as anthropologist Adam Kuper writes, “the history of human population began to come together again into a single process, for the first time since the origin of modern humans.” (1) We have called this “globalization.”

That’s a rough outline of how we currently tell the story of how the world got to be the way it is today. It’s now an interconnected world where you can eat McDonalds in Egypt, where Japanese cars are made in central Ohio, where you can click a button and have an item made by Chinese workers delivered to your doorstep the next day. A world where humans have had such a massive influence that even the wind and the weather bear our footprint. This is the world in which the six of you – Carolina, Zac, Gabe, Lydia, Mario, Nina are coming of age.

There are other ways of telling this story, and Genesis chapter 11 is one of them. It’s the final chapter of the opening section in Genesis scholars sometimes call “primordial history.” The stories are best understood as myth and parable. And if you think myth makes something less real, consider for a bit how profound an impact even a short phrase still has on our…

Facing grief, finding joy | January 26

Texts: Matthew 4:1-11; 5:13-14

Speaker: Amy Huser: Sustainability and Outdoor Education Director at Camp Friedenswald

About a year or so ago I was sitting in the Electric Brew, a coffee shop in Goshen, with Doug Kaufman, the Director of Pastoral Ecology for the Mennonite organization – Center for Sustainable Climate Solutions – talking about climate change – and he brought up the topic of lament as it relates to our work in this area, “It is very important to lament what is happening to the earth, and lament is a place that the church and pastors can really provide support for people – they know how to handle grief.” I paused, and then replied, “Pastors are really into lament, aren’t they? I’d rather talk about hope and action.” Luckily Doug didn’t get up and leave in offence at my almost impolite comment, although he may have wondered if I am a true Mennonite – speaking in such a blunt manner!

The truth is – at that point I’d developed a pretty strong aversion to the words lament and grief.

This was partially due to a pretty intense season of grief I went through a number of years before – around 2014 – grief over the lack of will or action in our social and political institutions to solve climate change – and along with that, the full realization that individual lifestyle changes could not come close to creating the conditions necessary for a sustainable world. We needed a complete transformation of our social and economic systems at a global scale. This realization hit me hard.

Mennonites (along with lots of other folks) like to work hard to make the world a better place. We highly value our sense of agency. One of the major faults of the sustainability movement is the…